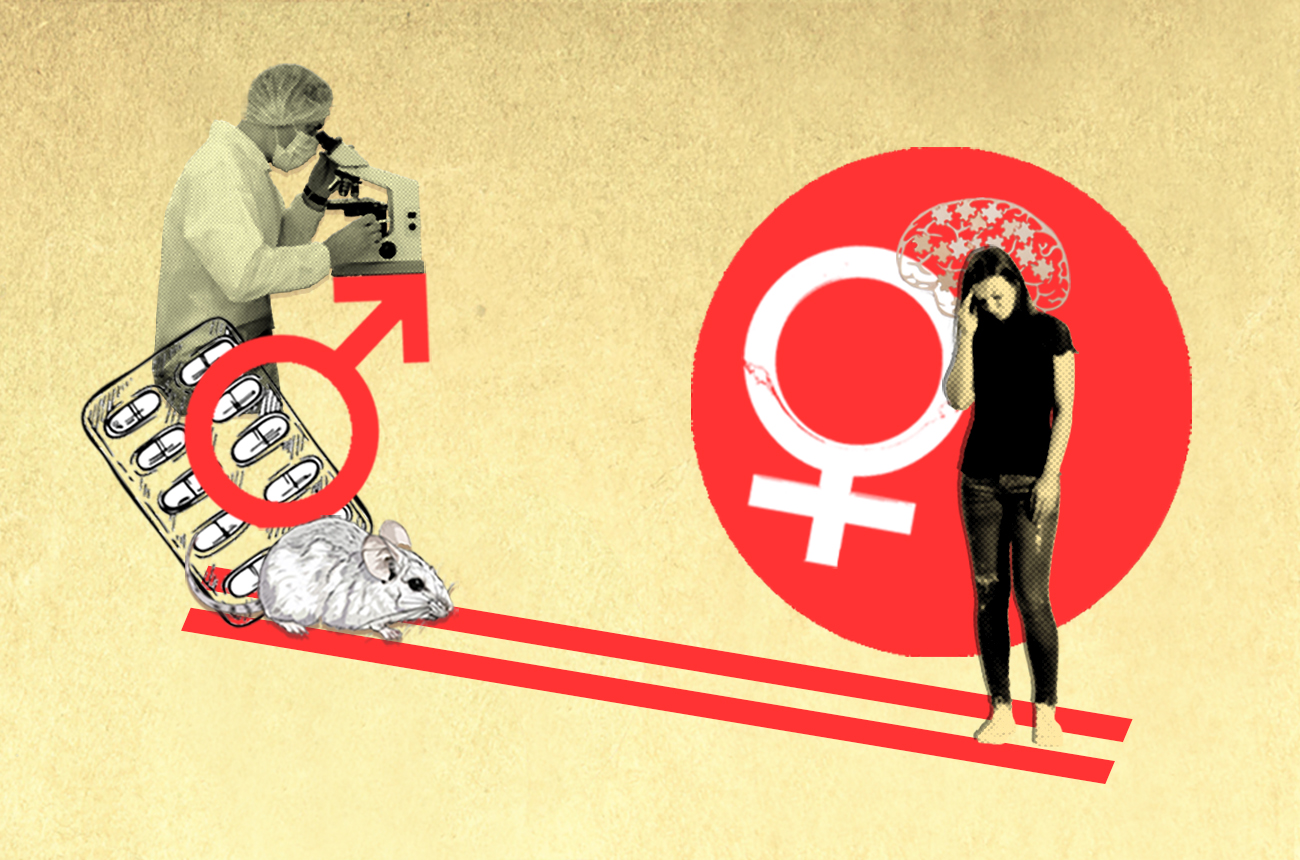

Women are often diagnosed later and report more side effects from medicine than men.

Keystone / Christian Beutler

Gender medicine is fighting to go mainstream, but funding gaps and political pushback are making it very hard. This isn’t stopping a pioneering group of doctors in Switzerland.

When Carolin Lerchenmüller became the first full professor of gender medicine in Switzerland last year, she told Swissinfo that she didn’t want to be a mascot. Her goal was to establish gender medicine as a “full-fledged academic discipline”.

The German cardiologist at the University of Zurich echoed those sentiments on Monday at the first Swiss Gender Medicine Symposium in Bern. “When you start, it is about having pioneers,” said Lerchenmüller. “But to survive, gender medicine can’t be associated with individual people. It needs to be institutionalised.”

Gender medicine is a new field that acknowledges that health and disease are affected by sex and gender, and that aims to integrate the biological and sociocultural aspects into research, medical practice, and education.

Sex refers to biological characteristics such as chromosomes, hormones and anatomy. These influence disease development and how drugs are metabolised, for example. Gender refers to social and cultural roles and identity. It influences, for example, how people seek care, how symptoms are communicated or perceived, and what kinds of risks or stressors individuals face in their daily lives. Source: UZH

A lot has been achieved towards that goal, Lerchenmüller told Swissinfo. There is now a Swiss Society for Gender Health, a national research project on gender medicine, and draft guidelines for considering sex and gender in cardiology.

But she says that globally the field faces headwinds. Since taking office US President Donald Trump has lodged a full-scale assault on diversity and inclusion in workplaces and research. US health and science agencies have scrapped funding for hundreds of projects and redacted webpages and guidance on gender diversity. Under pressure, pharmaceutical companies also toned down their advocacy and goals on diversity, equity and inclusion.

More

More

Switzerland now has a Professor of Gender Medicine. She’s here to stay.

Lerchenmülller hasn’t been directly impacted but “when the biggest public funder in the world makes massive cuts, it’s a problem for everyone,” she told Swissinfo.

She remains optimistic thanks to the large number of people who want to push gender medicine forward. Many US experts are now more eager to work with European collaborators, said Lerchenmüller. “Switzerland is becoming more visible in the field thanks to a decade spent urging leaders to take it seriously.”

This was on display at the first Swiss Gender Medicine Symposium held in Bern on October 20 and 21. Some 280 people across academia, industry, and public sector attended the two-day symposium, with 12% from outside Switzerland.

Gender medicine experts Carole Clair (left), Carolin Lerchenmüller (centre) and Cathérine Gebhard (right).

Swiss Gender Medicine Symposium/Sandra Blaser

Uphill climb

The gender medicine field in Switzerland still has its work cut out for it. Beyond political headwinds in the US, there’s very little funding available.

The Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) launched the first programme on “Gender Medicine and Health” at the end of 2023, with a budget of CHF11 million ($13 million), out of a total annual budget of CHF47 million. Some 140 proposals were submitted by 389 researchers. But there was only enough budget to fund 19 of them.

“The number of proposals received is a sign that people are interested and able to research the topic in Switzerland,” Lerchenmüller told the symposium audience. “We just need more funding to do it.”

Eleven million francs over five years is peanuts when one considers Zurich Zoo spent CHF57 million in two years on an elephant park. “For a topic that is so complex and has so much at stake, the amount of money spent is ridiculous,” said Antonella Santucionne Chadha, a doctor and neuroscientist who founded the Basel-based Women’s Brain FoundationExternal link. “We owe women a century of research.”

More

More

Drugmakers are finally making medicine for women

The national programme is still a step forward for Switzerland that has lagged behind other countries. It was only in 2019 that the University of Lausanne’s Centre of General Medicine and Public Health (Unisanté) became the first in the country to introduce courses on the influence of sex and gender on health in its medical curriculum. This was far after some universities in the US, Germany and Sweden did so.

Depolarising gender

The biggest challenge, says Lerchenmüller, is still getting people to understand gender medicine.

“Gender might be a polarising word to some people but that’s because people might not understand what it means in the context of medicine,” said Lerchenmüller.

For surgeons like Guido Beldi at Bern’s largest hospital Inselspital, there are very practical and life-saving reasons to consider sex and gender, specifically in the case of liver transplants.

More

More

How Trump’s attack on diversity could derail drug development in Switzerland

He cites as an example that adrenaline is released faster in male patients, which protects them when the blood pressure drops during surgery. However, women secrete cortisol, which is the main “stress hormone”, for longer periods of time, which helps in healing and could explain why women usually recover faster from surgery.

The differences go beyond anatomy. He told the symposium audience that women tend to be referred later for surgery and are offered the most advanced types of surgeries less often. “The sex of patients determines how they respond to surgery; gender indicates when and how patients are treated,” said Beldi. Taking biological and social factors into consideration ensures patients receive personalised care tailored to them.

But there is still a lot that isn’t understood about sex and gender differences, especially at different ages that requires further research, said Beldi.

Doctors pioneering the field in Switzerland are aware that gender medicine is still a politically charged term. They hope to make the symposium an annual event that isn’t just for health professionals but brings politicians and business leaders along with them.

“In Switzerland, there is a risk of backlash when we talk about gender, especially when we see what is happening in the US,” said Carole Clair, a physician at UniSanté in Lausanne and the president of the steering committee for the national programme on gender medicine. “We need to depolarise it.”

Edited by Virginie Mangin/sb